How, when and where did you two first meet?

G – We met on a night out at The Academy in Bristol. I was just in my second year at UWE, studying Fashion and Chris (who was living and working in London) came to town to catch up with friends. It was a complete fluke that we met, two twenty somethings, a lot of beer and a mutual love of hip-hop. After that night Chris came back to Bristol the following Saturday and we went out for dinner. It was instant love and the best friendship. That was fifteen years ago and we’ve barely been apart since.

When did it occur to you that your styles had a certain compatibility, that could work well together in collaboration?

G – Even very early on in our relationship there was so much creativity. On the weekends when I would visit Chris in London, he was already starting to make a name for himself with his art, even though he was working full time as a graphic designer. He would take me to exhibitions, introduce me to other artists and it was a really special and exciting time. Alongside completing my degree, for those first two years of our relationship I would help Chris with organising his exhibitions, help with printing and assist him with his murals. He put a lot of trust in me and I learnt so much. We have basically been collaborating since the day we met. We bounce ideas off of each other, our passions are very similar. We completely understand each other as artists as well as individuals and I think that’s a very special thing.

C – We both spent quite a few years developing our own original styles. We were both creating very different works stylistically and technically, but I think it was only when we both had individual identity, that we realised that a lot of the themes were similar. So, putting them together at that point was easy.

Roughly how many pieces have you created together?

C– Loads. No clue how many? Dozens, including outside murals, gallery pieces and print editions.

Have you ever hosted a joint exhibition?

G -We’ve done a lot of projects together. My proudest collaboration was our exhibition we did a couple of years ago in Chicago. The show was called ‘Two Sides’, it was a combination of paintings as individual artists and collaborative works. The concept was two sides of a story, a relationship, coming together to create something new and exciting. The trip was amazing and the show was really well received. Chicago is an incredible place for art. We met so many amazing people and I can’t wait to be able to go back again.

How, in practice, do you work on a piece – what’s the process?

C – Initially I just go wild on a canvas, just so I’m not starting on a blank space. Then I plan what I’m going to add to that, but I deliberately don’t create a finished plan, just a starting point really. I want to create in a way that’s more organic. Usually, it’s not until your actually painting it that the piece will tell you what it wants.

G – My process is lengthy. I like to build layers of paint and a lot of details. I use brushes with mainly acrylic paint. I want to show different techniques and layering in the work. A lot of the time I start with an idea of what I want to create but as I start working on a piece it will almost ‘tell me’ what it needs as it develops. It sounds crazy, but you learn so much from each thing you create and you take that forward into the next work. Everything is always evolving.

When working on individual pieces, do you still get involved in each other’s work?

G – YES, all the time! Even if the other doesn’t want or care for the others opinion. We work well together, but we are both quite strong-willed individuals. At the time it can cause some tension in the household but I’d rather we were honest and critiqued each other’s work, encouraging each other to be better artists. It means that when one of us says the others work is good, its honest and not just because we don’t want to hurt the others feelings.

C – It’s hard because you’ve got to know when to say something and when to bite your lip. Often, I’ve seen Gemma do something in a completely alien way to me then, a couple days later it’s this magical, beautiful completed rose or something. We learn to trust each other’s judgement but also trust each other’s creative freedom.

Girls and nature motifs seem to occur in both your works – are there any other similarities?

G – There’s probably loads, I think we’re just too close to see it. Art really is our life and I feel so blessed to be on this creative journey together. I think we are always going to subconsciously feed into each other’s creative psyche, we are husband, wife, great friends and colleagues.

Has the other’s style and technique influenced your own style and technique?

G – Chris has been a huge influence on me as an artist. He’s taught me a lot about this business. He has supported me and encouraged my development as I sometimes struggle with self-confidence issues. I think our styles and techniques have remained individual but we also complement each other well within the work.

C – Gemma teaches me patience and subtleties, and how to use multiple mediums.

Which art movements, if any, have been an inspiration to you?

C – Around the early 2000s I found myself in the middle of this new movement called street art. One day I was just doing my thing, next day it’s this whole scene. It has been amazing to discover a community of people doing similar work to me and share ideas and good times.

I do find a lot of inspiration in art history. I’m obsessed with POP ART and I’m inspired by the work of Renascence artists and Pre Raphaelites, so whenever we visit a new city the first stop is almost always a Museum.

G – For me it’s never really been one movement, I’ve always been drawn to painter’s technique. Weirdly, during this past year with various lockdowns I took several online art courses and one was on Abstract Expressionism, a movement which in the past just didn’t interest me. Now I’m hooked on the emotion within the abstraction and the movement of paint. I’m hoping I can take what I’ve learn forward into my own practice.

What does Chris most admire about Gemma’s work and approach, and vice versa?

G- I adore Chris’ storytelling in his work. He’s great a conveying emotion in a contemporary way. So many people connect to his work and he has a vast number of collectors who love his paintings. I admire the bravery and boldness within the work, contrasted with a real sensitivity and sometimes sadness. That’s a powerful combination that makes good art.

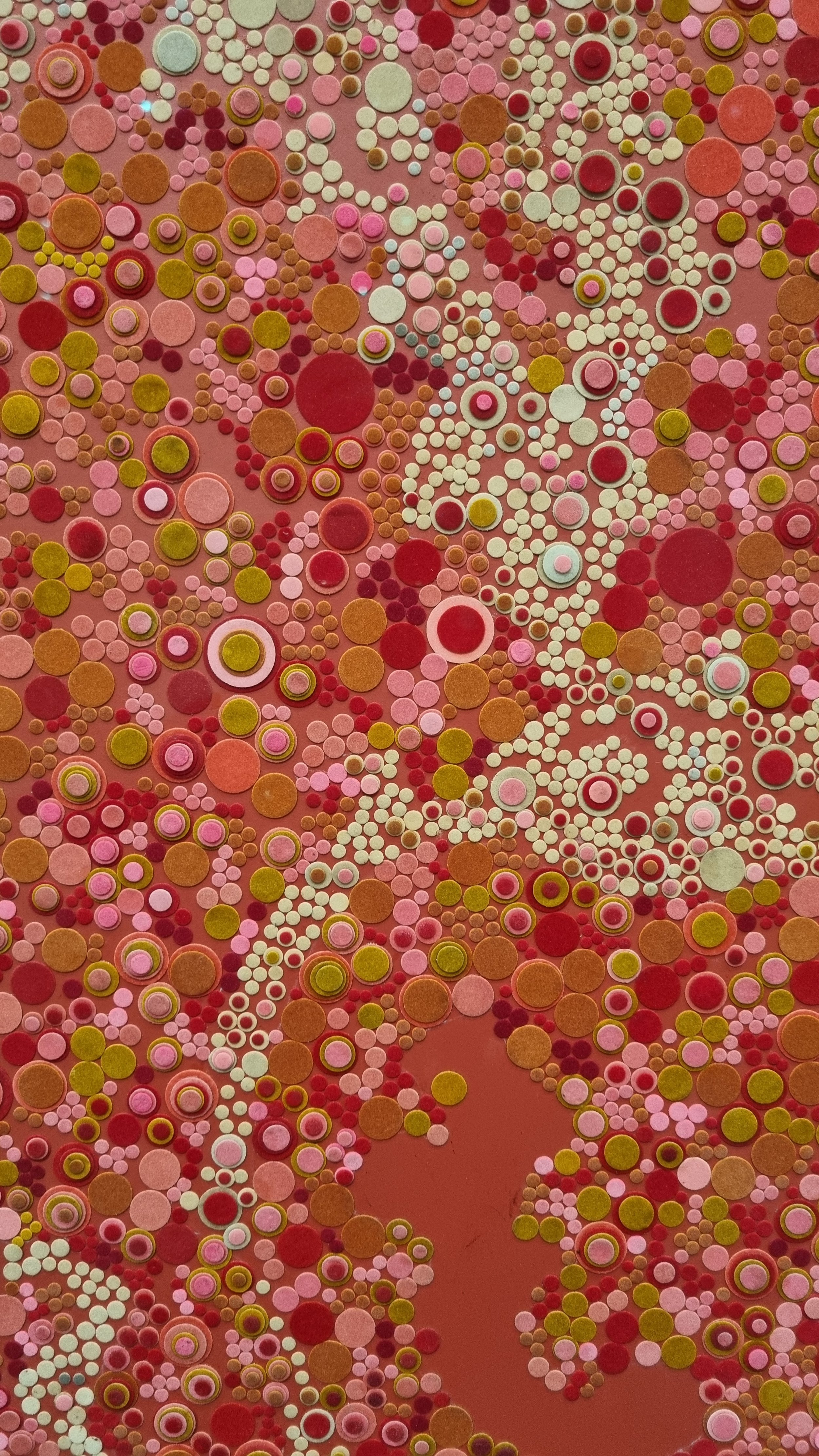

C – I’m in awe of Gemma patience and attention to detail and in that regard we’re totally different. I’m much more spontaneous and reactionary. Imagine having the skill and technique to paint anything you could dream up, that’s her, pure alchemy.

Do you have a favourite piece that you’ve collaborated on?

G- Probably ‘Muse’. She was created for our Chicago exhibition but I think most of our collaborative work for that show was pretty strong.

C – Yeah ‘Muse’ is one of the standouts, but couple pieces from that collection were bangers.

Where about do you work?

C – We are really lucky to have a great set up at home. We have our own spaces. Gem’s inside the house and we turned our garage into my studio. We did have a separate studio at one point but it made more sense to use the space we already had. It really works well for us.

If you weren’t artists, what would you be?

G – Stunt Woman.

C – Clown.

How have you managed to keep afloat and positive during the past year?

G – When the pandemic first happened, I thought well, this is scary but we’re used to being at home all the time, I’ll just use the time and make loads of great work. But the truth is we both found it really hard to be productive and because of all the uncertainty day to day our mental health really took a dive and it became impossible to work. Since then, there have been good days when the paint is flowing and weeks when it has been more of a challenge. I took online courses on art history, which was a great way to keep me connected to being an artist even though I couldn’t make any art. Now nearly a year later we have found more of a rhythm of working. We still are nowhere near as productive as before and there is still a lot of uncertainty in the future especially in the creative industry. At the moment we are finding a balance between creating and being kind to ourselves.

The best and worst things about living with a fellow artist are……

G – The best: Having someone who 100% knows your needs. Art takes time and a lot of dedication. You need someone who understands why you have been in the studio for days on end and can deal with the tantrums (artist temperament).

The worst: The mess. I’m organised and a neat freak, someone’s else not so much.

C – The best; both being on exactly the same wavelength and workflow. Being able to bounce ideas off each other.

The worst: the artist temperaments!!!

Any plans for the future?

C – I have a plan for a big show in 2 parts, maybe at 2 galleries or in 2 separate cities or countries. It’s pretty vague and it’s hard to make concrete future plans at the moment, but I’m going to start work on it now so can put into action once I’m able.

G – I want to create bigger and better work. Another solo show…But right now I’ll settle for getting through to the other side of this pandemic, a cold beer on a hot day with my friends in the pub and a hug from my Mum.